It’s Time to Move On

By Dan Wall — EVP, Corporate & Regulatory Affairs

For the past three years, Live Nation has been embroiled in a DOJ investigation and lawsuit that sought to reverse the 2010 merger that brought together Live Nation, the concert promoter, with Ticketmaster, the primary ticketing company. When Jonathan Kanter, the DOJ Antitrust Chief under President Biden, announced the case, he broke from usual DOJ practice and announced on Day One that “it was time to break up Live Nation and Ticketmaster.” He also told the American public that the merger and its attendant evils were responsible for high ticket prices and fees.

Of course, none of this was true. The claim that Live Nation and Ticketmaster are responsible for high concert ticket prices and fees was, and is, false. On the eve of trial, DOJ has no evidence of that, and its argument has become that it doesn’t need to prove higher prices. We’ll see. But the bigger fiction was that this case could or should result in a court order breaking up Live Nation and Ticketmaster. We’ve always said that was implausible and improper, and yesterday’s summary judgment decision should put that false promise to rest.

Start with the fact that monopolization cases hardly ever result in divestiture remedies. The last time it happened was in 1980, when AT&T agreed to be broken up to resolve a monopolization case that was in the late stages of trial. In the 1990s, the DOJ briefly had an order compelling a breakup of Microsoft, but that was reversed on appeal. Instead, the normal remedy for the kinds of claims lodged against Live Nation is an injunction prohibiting a business practice to the extent it is unlawful. For example, in the Google Search case, Judge Amit Mehta of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia rejected the DOJ’s request to force Google to spin off Chrome, and instead enjoined some — but not all — forms of exclusive default agreements. This may happen again in the Google AdTech case, where after prevailing on liability, DOJ asked the court to order the divestiture of Google’s ad exchange (AdX) and open-source its publisher ad server (DFP). No decision has issued yet, but at the November 21, 2025 remedies hearing, Judge Leonie Brinkema indicated that she would first consider whether behavioral remedies are sufficient and turn to structural remedies only if she concluded they are not.

The governing legal standards require judges to take this approach. This is the legacy of the DOJ’s failed attempt to break up Microsoft, and was reaffirmed in the Google Search decision. Those cases hold that “‘divestiture is a remedy that is imposed only with great caution, in part because its long-term efficacy is rarely certain.’”[i] They note it has mostly been used to “terminat[e] monopolies formed by mergers and acquisitions,”[ii] a rationale that cannot apply here because, by the DOJ’s own telling, Ticketmaster was already a ticketing monopoly when it combined with Live Nation. The merger was nevertheless approved because, in the DOJ’s own words at the time, it was “sure to benefit concertgoers, artists, and the industry as a whole.”

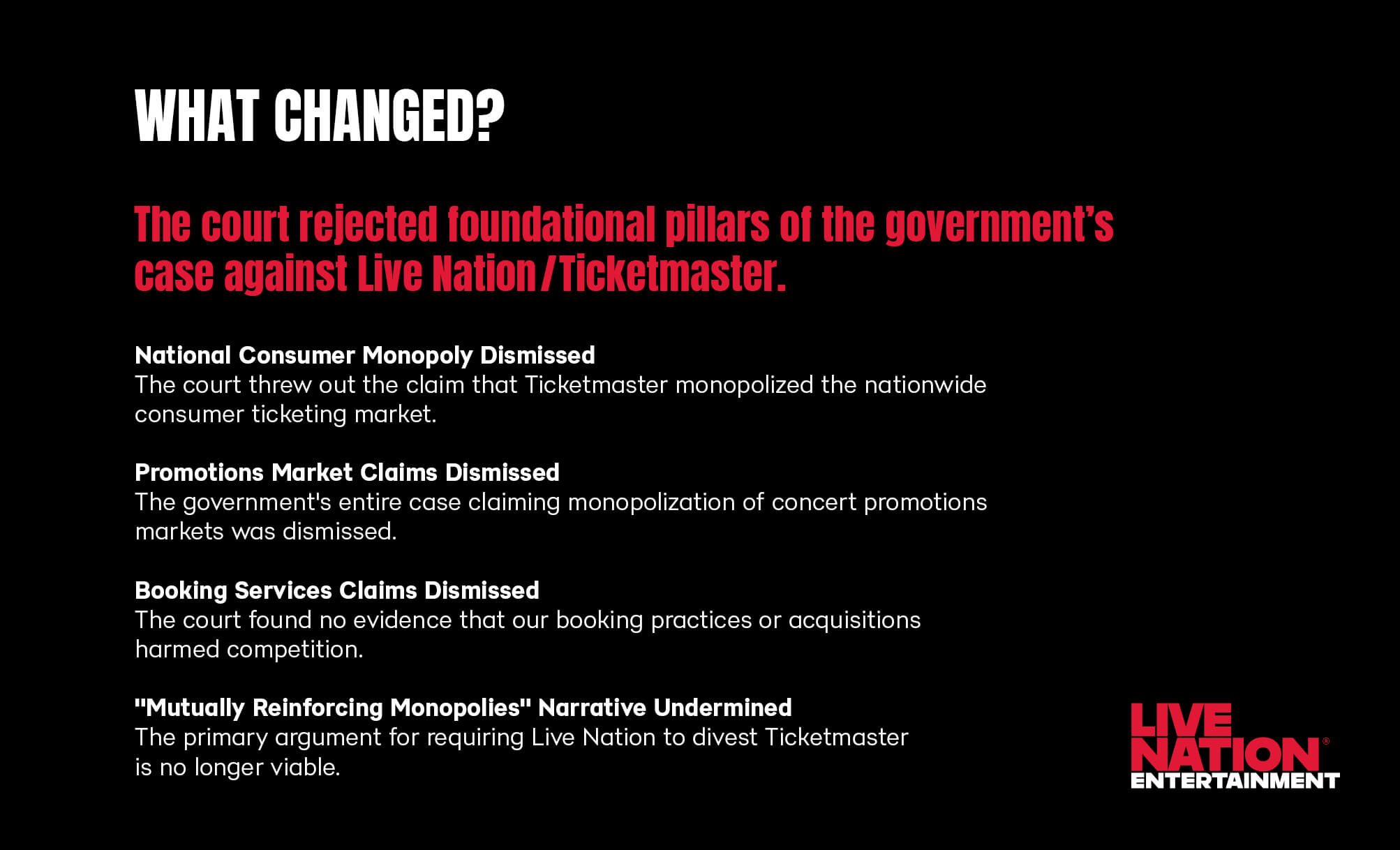

Even before yesterday’s summary judgment decision, it was evident that DOJ could not meet the Microsoft/Google “causation” requirement that the defendant’s monopoly power was rooted in unlawful conduct that could only be remedied by divestiture.[iii] And yesterday, the court substantially narrowed the case.

It is the dismissal of the concert promotion claims that undermines any serious argument for breaking up Live Nation and Ticketmaster. First, it ends the narrative that concert promotion and ticketing are “mutually reinforcing monopolies.” There was never much substance to that contention, but the idea at least was that the two monopolies propped up one another. Now DOJ has failed to prove there is a concert promotion monopoly. DOJ can’t make this reinforcing monopolies argument anymore.

Second, it means that separating Live Nation the concert promoter from Ticketmaster would not serve any remedial purpose, let alone be a legally permissible remedy. The case is now about three things: long-term exclusive ticketing contracts, a discrete ticketing deal Ticketmaster has with Oakview Group, and Live Nation’s policy of not renting its amphitheaters to rival promoters. None of those claims, nor even all three taken together, warrants more than standard injunctive relief.

Cases in this posture nearly always settle, and with the prospect of structural relief off the table, that is what should happen in this case now. Live Nation is ready to make that happen with DOJ and any State Attorney General committed to realistic, common-sense solutions to the remaining issues. We understand that any settlement needs to be meaningful for our venue customers, for artists, and of course for fans. That is what we want, too. Despite the constant criticism we receive from some quarters, Live Nation and Ticketmaster have led the industry in promoting reforms that artists and fans care about. We hope and expect that a resolution of this case will extend those efforts.

[i] United States v. Google LLC, 2025 WL 2523010 at *55 (D.D.C. Sept. 2, 2025) (quoting United States v. Microsoft Corp., 253 F.3d 34, 80 (D.C. Cir. 2001).

[ii] Id.

[iii] See Google, 2025 WL 2523010, at *55 (“After two complete trials, this court cannot find that Google’s market dominance is sufficiently attributable to its illegal conduct to justify divestiture.”).